Now that we have a powerful lens that’s always focused on the deepest regions of the universe, our definition of “surprise” has changed a bit when it comes to astronomical images. Indeed, it’s no longer “weird” when NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope discovers a brilliant ancient piece of space. At this point, we know that nothing less than innovative machine.

Instead, every time he sends back a stunning cosmic image, it seems to elicit more “JWST strikes again!” feeling Still, our jaws legitimately drop every time.

In any case, this dissonant version of “surprise” happened again – to a rather extreme degree. Last week, scientists unveiled a brilliant JWST view of a cluster of galaxies merging around a massive black hole that hosts a rare quasar — aka the inexplicably bright jet of light bursting from the chaotic center of the void.

I know there’s a lot going on here. But the team behind the find believe it could go even further.

“We think something dramatic is about to happen in these systems,” Andrei Weiner, a Johns Hopkins astronomer and co-author of a study about the scene, which will soon be published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, said in a statement. For now, you can read a detailed description of the discovery in an article published on arXiv.

Artist concept of a galaxy with a bright quasar in the center.

NASA, ESA and J. Olmsted (STScI)

What’s particularly fascinating about this portrait is that the quasar at hand is considered an “extremely red” quasar, meaning it’s very far away from us and thus physically rooted in a primitive region of space that dates back to the beginning of time.

Essentially, because it requires it time for light to travel through space, every stream of cosmic light that reaches our eyes and our machines is seen as it was long ago. Even moonlight takes about 1.3 seconds to reach Earth, so when we look at the Moon, we see it 1.3 seconds in the past.

More specifically, in the case of this quasar, scientists believe that it took about 11.5 billion years for the object’s light to reach Earth, meaning that we see it as it was 11.5 billion years ago. This also makes it, according to the team, one of the most powerful of its kind observed from such a gigantic distance (that is, 11.5 billion light years).

“The galaxy is at this perfect moment in its life, about to transform and look completely different in a few billion years,” Weiner said of the sphere in which the quasar resides.

Analysis of galactic rarity

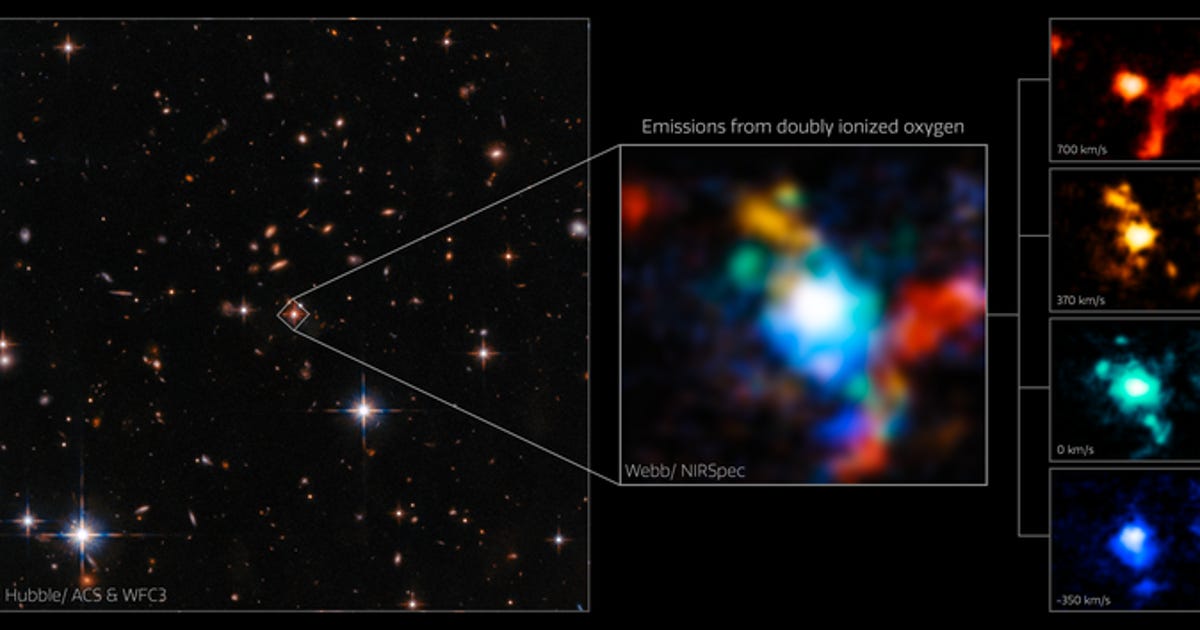

In the colorful picture presented by Weiner and other researchers, we are looking at several things.

Each color in this image represents material moving at a different speed.

ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, D. Wylezalek, A. Vayner & Q3D Team, N. Zakamska

Left is a Hubble Space Telescope view of the region the team studied, and middle is a zoomed-in version of the spot targeted by JWST. Take a look at the far right of this image, where you can see the four individually color-coded fields, and you’ll be analyzing different aspects of the JWST data broken down by velocity.

For example, red things move away from us, and blue things move towards us.

This classification shows us how each of the galaxies involved in the spectacular merger is behaving – including the galaxy that hosts the supermassive black hole and its companion red quasar, which is essentially the only galaxy the team expected to detect with the help of multi-billion funds NASA instrument.

“What you see here is just a small fraction of what’s in the data set,” Nadia L. Zakamska, an astrophysicist at Johns Hopkins and co-author of the study, said in a statement. “There’s too much going on here, so we’ve highlighted what really is the biggest surprise first. Every drop here is a baby galaxy merging with mom’s galaxy, and the colors have different speeds, and it’s all moving in an extremely complex way.”

Now, Zakamska says, the team will begin to untangle the movements and improve our view even more. However, we are already looking at information that is much more incredible than the team expected from the beginning. Hubble and the Gemini-North telescope have previously hinted at the possibility of a transiting galaxy, but haven’t exactly hinted at the swarm we can see with JWST’s wonderful infrared equipment.

In another spectacular image taken by Webb’s Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam), hundreds of background galaxies of varying size and shape appear near the Neptune system.

EKA

“With previous images, we thought we were seeing hints that the galaxy might be interacting with other galaxies on its way to merging, because their shapes are being distorted in the process,” Zakamska said. “But after we got Webb’s data, I thought, ‘I have no idea what we’re looking at here, what kind of thing!’ We just looked and looked at these images for weeks.”

It soon became clear that JWST was showing us at least three separate galaxies that were moving incredibly fast, the team said. They even suggest that it may mark one of the densest known regions of galaxy formation in the early universe.

An artist’s impression of the quasar P172+18, which is associated with a black hole 300 times the size of the Sun.

ESO/M. Kornmesser

Everything about this complex image is mesmerizing. We have a black hole that Zakamska calls a “monster,” a very rare jet of light shooting out of that black hole, and a group of galaxies on a collision course, all seen as they were billions of years in the past.

So, dare I say it? JWST strikes again, offering us an extremely valuable space vignette. Qiu, jaw.